The Democratic Socialists’ of America 2019 National Convention was excellent and there has been a surfeit of great articles) about it. But despite all the writing about the convention, I had a thought which I have not seen addressed: what do the delegates’ ballots tell us about the internal structure of the new NPC? In particular, will the structure expressed in the ballots correspond to the candidates’ factional endorsements?

Appendix

So long story short, my task in code is to

- process the data from all the ballots,

- find how closely ranked each candidate is to each other candidate on average.

- plot these results in a social network, and

- use community detection to find structure in the network.

So here is my code with minimal comment. Please be forgiving as this was coded up in a hurry! Feel free to reach out with questions or thoughts.

0. Setup

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library(tidyverse))

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library(tidygraph))

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library(ggridges))

suppressPackageStartupMessages(library(igraph))

library(ggraph)

options(max.print = 500)

winners <- c(

'Abdullah Younus',

'Austin Gonzalez',

'Blanca Estevez',

'Dave Pinkham',

'Erika Paschold',

'Hannah Allison',

'Jen McKinney',

'Jennifer Bolen',

'Kristian Hernandez',

'Maikiko James',

"Marianela D'Aprile",

'Megan Svoboda',

'Natalie Midiri',

'Sauce',

'Sean Estelle',

'Tawny Tidwell'

)1. Process the Data

The new pivot_longer function in the tidyr package is indispensible. I’m really glad to see its addition into tidyr. Side note: I’m not distributing the data with this analysis because I don’t own it. But I have been told you can download it from the DSA forums if you wish to run this or another analysis yourself.

dat_wide <- read.csv('ballots.csv', header = TRUE, stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

dat_wide[, c('Voter.First.Name', 'Voter.Last.Initial')] <- list(NULL)

names(dat_wide) <- c('voter', 'chapter', 1:32)

ballots <- pivot_longer(

dat_wide,

cols = -c(voter, chapter),

names_to = 'rank',

values_to = 'candidate'

)

ballots <- ballots[ballots$candidate != " ", ]

ballots$rank <- as.integer(ballots$rank)

ballots$candidate_is_winner <- ballots$candidate %in% winners2. Compute Candidates’ Distances to Other Candidates

Here I use merge from the base library because I think its syntax is a lot nicer than dplyr’s join syntax.

An important remark here is that I only incorporate rank distance information when it’s recorded in an observation. This is despite the fact that it’s plainly obvious that rankings are missing data, specifically what is known as either missing at random or missing not at random. We can gain information from analyzing missing data at the same time as present data. But that is way out of the scope for this analysis, perhaps a future one. 🙂

rank_pair <- merge(

ballots[, c('voter', 'candidate', 'rank')],

ballots[, c('voter', 'candidate', 'rank')],

by = 'voter',

suffixes = c('_from', '_to')

)

rank_pair$voter <- NULL

rank_pair$distance <- abs(rank_pair$rank_to - rank_pair$rank_from)

rank_pair_short <- rank_pair[rank_pair$candidate_from > rank_pair$candidate_to,]

rank_diff_mean <-

rank_pair_short %>%

rename(ego = candidate_from, alter = candidate_to) %>%

group_by(ego, alter) %>%

summarize(weight = mean(distance))

dat_gph <- rank_diff_mean2.5 The Special Sauce

dat_gph$weight <- 1/(dat_gph$weight^4)Here I transform weight --> (1/weight)^4.

Why reciprocal? The weight is a representation of closeness, but rank distance is an expression of distance. So they are negatively related to each other.

Why the fourth power? The fourth power here is spreading candidates out from each other, inflating distances from farther away candidates. What’s going on here is that the range of mean rank distance is too small to tell clusters apart. No spreading leads to a network where you have one cluster. Lower spreading than fourth power leads to a network that is more or less degenerate, spread out only in a line.

Try it out and let me know what you think might be a better approach.

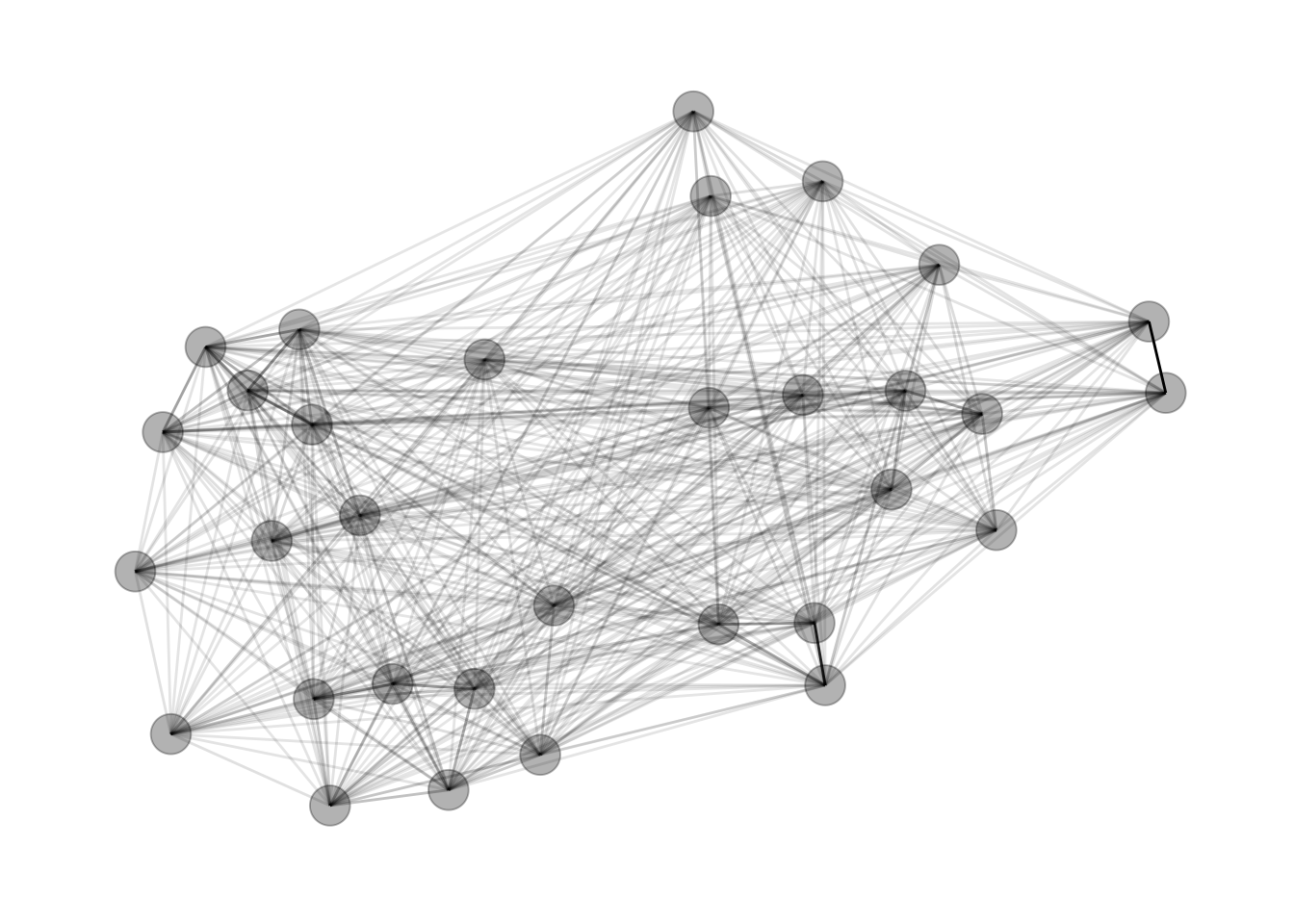

3. Plot the Network

Like I noted before, I use the Fruchterman-Reingold force-directed layout.

gph <- graph_from_data_frame(dat_gph, directed = FALSE)

gph_tdy <- as_tbl_graph(gph)

set.seed(4793461)

gph_tdy %>%

mutate(community = as.factor(group_infomap(weights = weight))) %>%

ggraph(layout = 'fr') +

geom_edge_link(aes(alpha = weight), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(size = 7, alpha = .3) +

theme_graph()

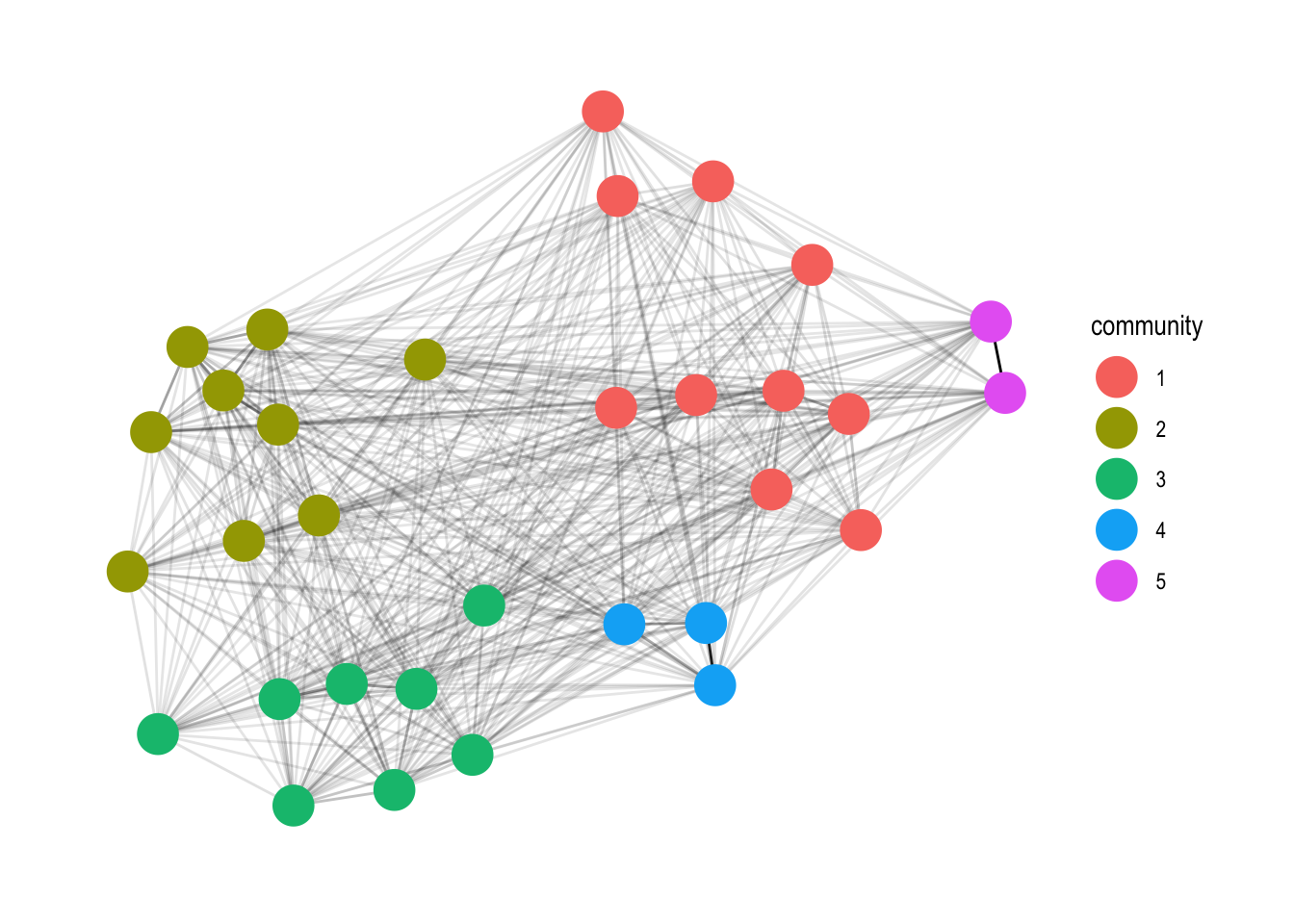

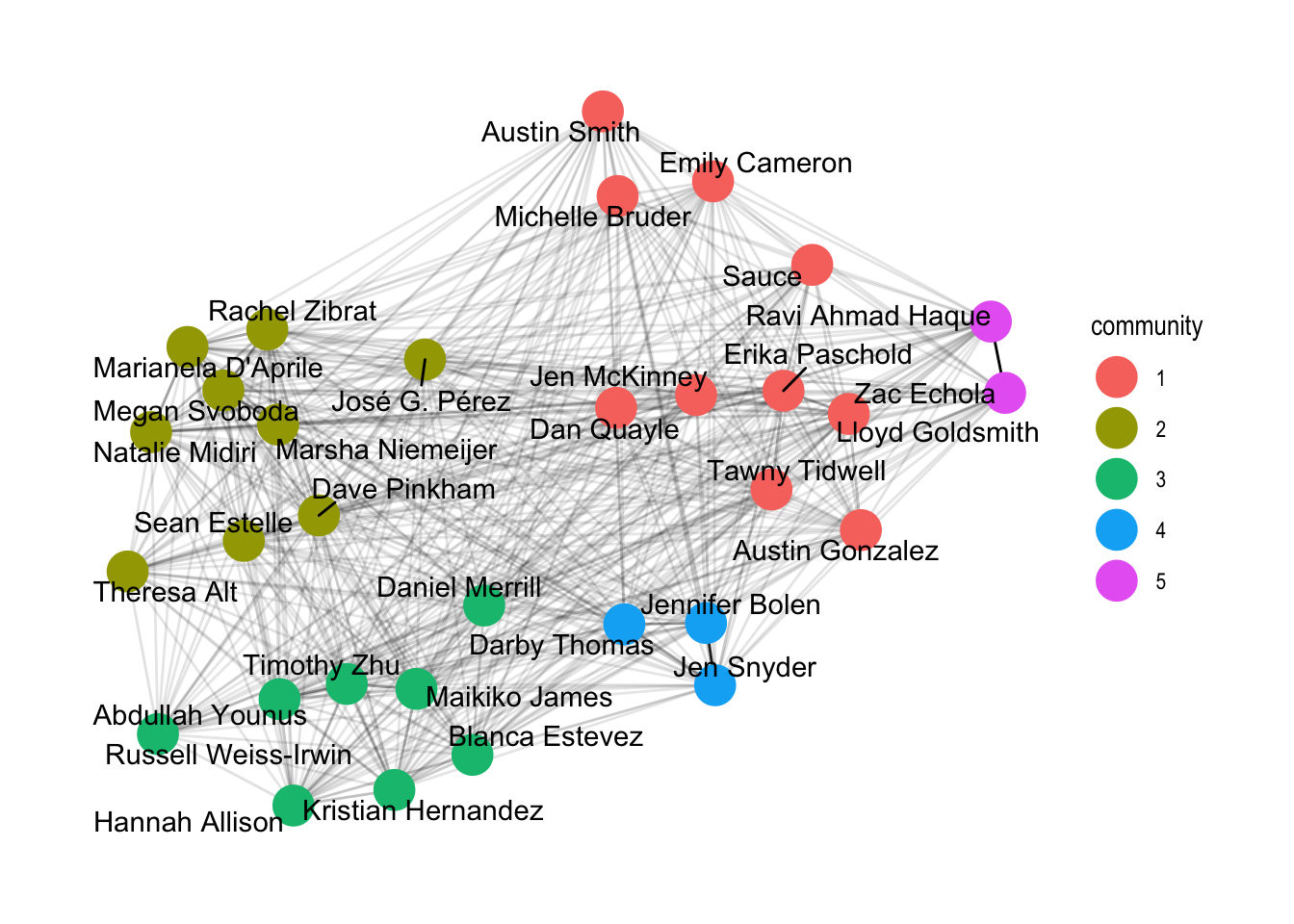

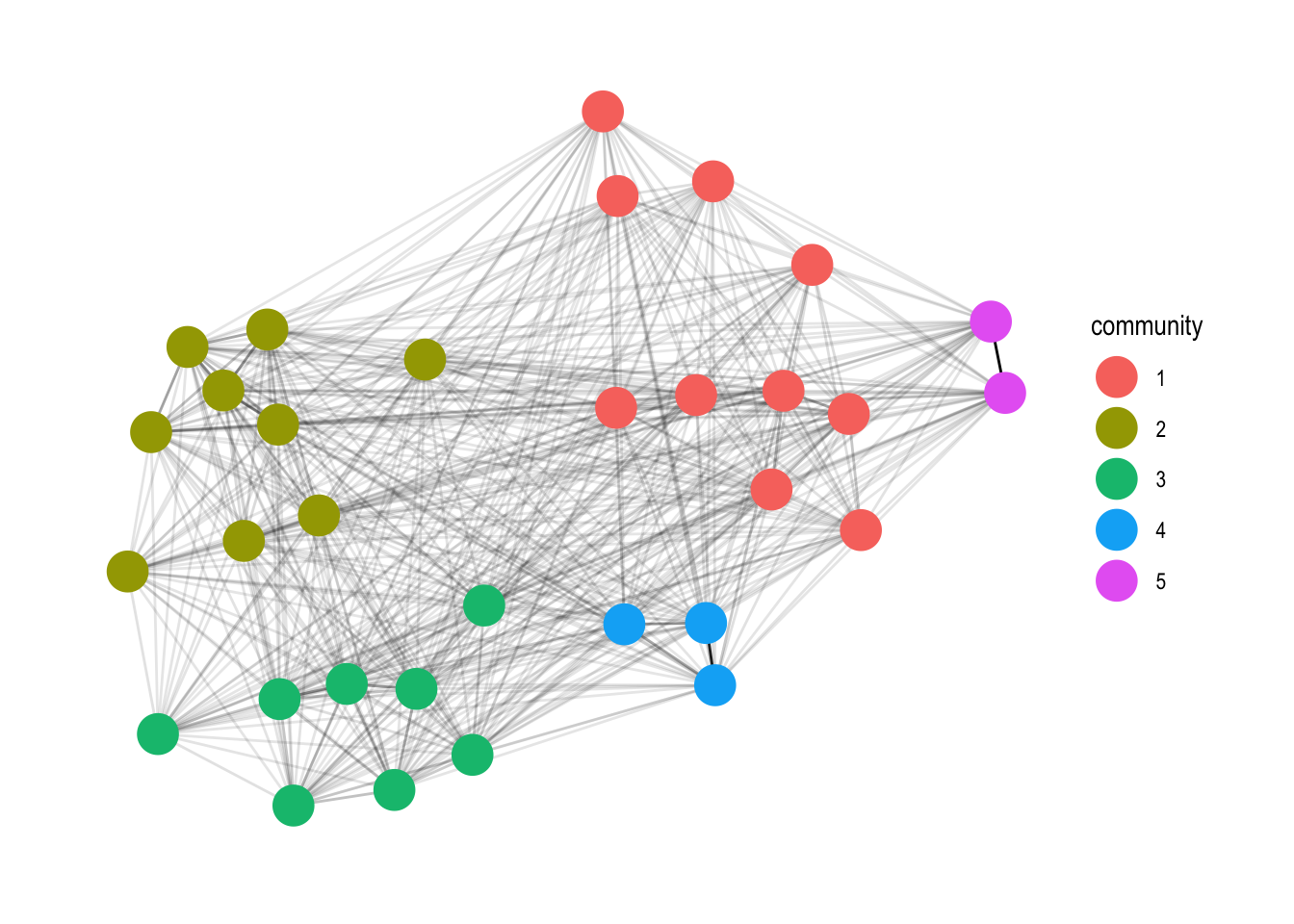

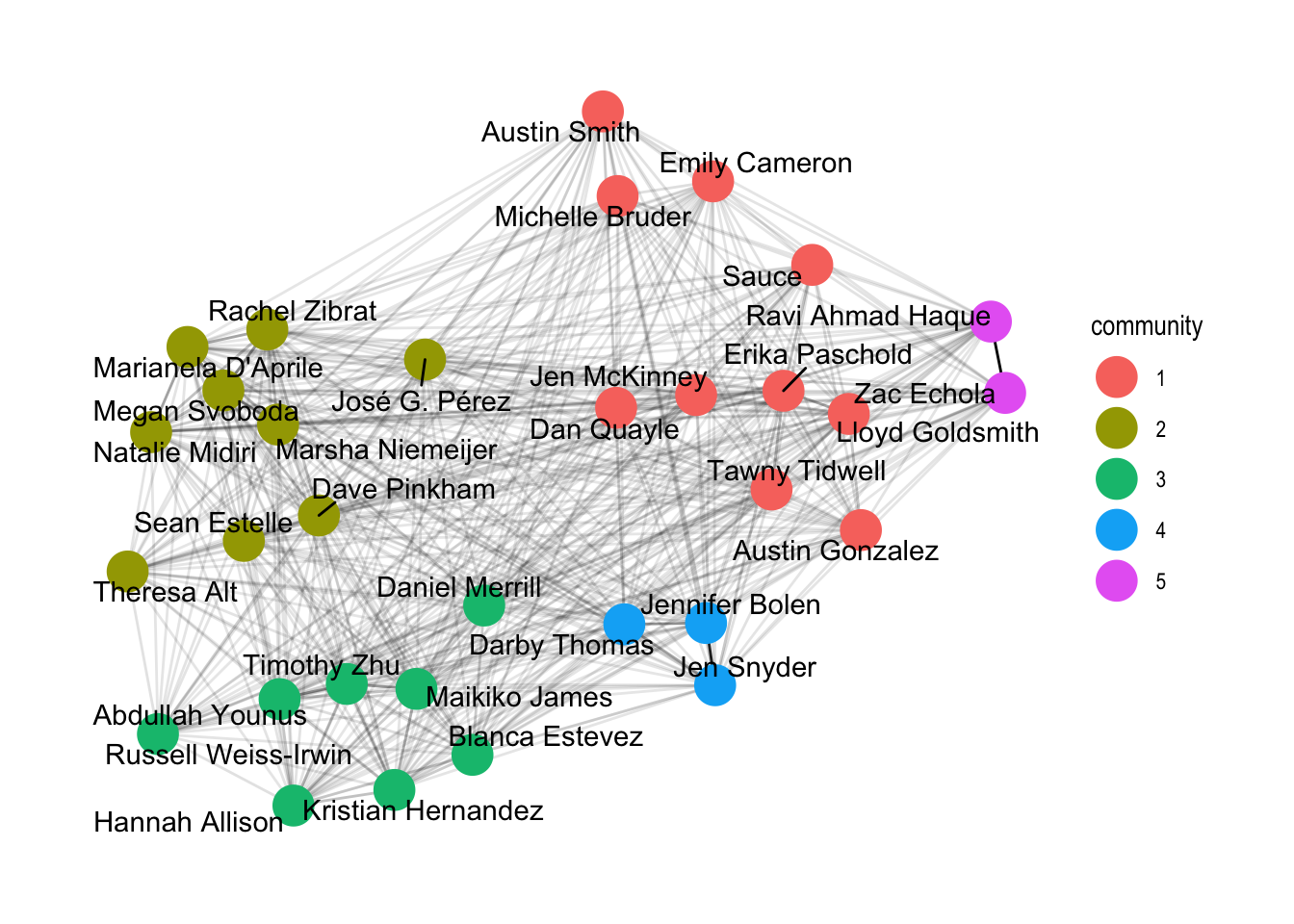

4. Plot the Communities

Add in the community computation with the group_infomap function.

set.seed(4793461)

gph_tdy %>%

mutate(community = as.factor(group_infomap(weights = weight))) %>%

ggraph(layout = 'fr') +

geom_edge_link(aes(alpha = weight), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(aes(colour = community), size = 7) +

theme_graph()

set.seed(4793461)

gph_tdy %>%

mutate(community = as.factor(group_infomap(weights = weight))) %>%

ggraph(layout = 'fr') +

geom_edge_link(aes(alpha = weight), show.legend = FALSE) +

geom_node_point(aes(colour = community), size = 7) +

geom_node_text(aes(label = name), repel=TRUE) +

theme_graph()

Social Networks

I decided to tackle it with social network analysis. Scientists use social networks to analyze the ways individuals connect with each other and how these connections form larger structures. For example you might build a social network where each node is a person and nodes are connected by an edge representing friendship.

Here are two social networks representing high school friendship data, courtesy of Thomas Lin Pedersen.

Social networks can be directed (think Twitter follows, unilateral); undirected (think Facebook friendships, reciprocal); weighted, where connections have amounts; and unweighted, where you’re either connected or not. For example, a directed, weighted network is formed of individuals’ Venmo payments.